Lahore literary festival - a safe place for dangerous ideas

February 25, 2016, 06:00

‘How else could you experience so much of the world in one weekend?’ In defiance of security concerns, the Lahore literary festival retained a mood of determined cheerfulness.

Would it go ahead or not, and if so where? There can’t be many public events that have been forced to confront such fundamental questions less than 24 hours before curtain-up, but the organisers of the fourth Lahore literary festival faced down the authorities’ concerns about security with a quick change of venue and a one-day programme reduction, prompting Pakistani journalist and novelist Mohammed Hanif to remark wrily, “The government says we can’t give security on Friday but we can do it on Saturday and Sunday. Why is it a security threat on Friday and not on Saturday?”

Hanif, whose 2008 debut novel A Case of Exploding Mangoes was a satire centred on the death of Pakistani president General Zia in a mysterious plane crash, was speaking at a session on George Orwell, whose presence loomed large over the festival as rumours swirled as to whether the clampdown was due to genuine concerns about a terrorist attack or to a standoff between the regional government and protesters against the damage being inflicted on this historic city by the construction of a new metro line.

Whether jitters or vindictiveness were to blame, the resulting atmosphere of determined cheerfulness chimed with the themes of an intelligently programmed festival, free to all comers, whose subjects ranged from “Creativity, chaos and capital: the future of the metropolis” to “Foundering freedoms” and, not least, “Satire as self-defence.”

There’s no denying that Pakistan is a dangerous place, caught between an authoritarian government and Islamist insurgents. One person who would undoubtedly have attended the festival was Sabeen Mahmud, the director of an edgy cafe-bookshop in Karachi, who was shot dead in her car last April. Another was Shakil Auj, dean of Islamic studies at Karachi University, who was assassinated six months earlier, allegedly for writing a book that explored the idea that Muslim women should be allowed to marry outside their religion. As a Pakistani writer remarked, “We all have friends who have been killed.”

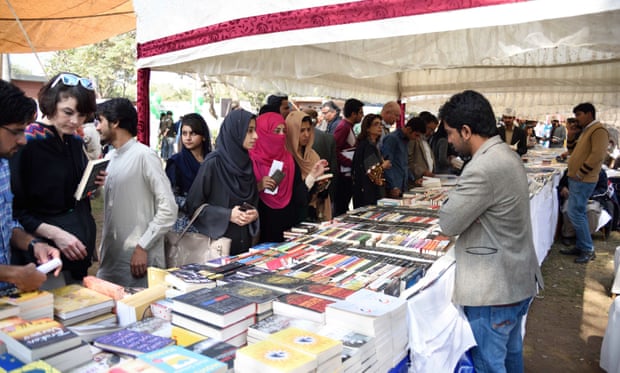

But both deaths happened in Karachi, and Karachi is not Lahore, where the most immediate threats to life and limb are the jostle of tuk-tuks and motorbikes on the roads and the tangles of power cables crisscrossing pavements in the creative chaos of a teeming capital. Speaker after speaker pointed out that the thing most greatly to be feared is fear itself – and there was little evidence of it in the upmarket Avari hotel, where thousands of people poured through police checkpoints to immerse themselves in a programme that mixed English and Urdu, pop and politics, and to pore over trestle tables groaning with books on the hotel lawns.

While politicians such as the former Pakistani foreign minister Hina Rabbani Khar and the onetime president of Kyrgystan Roza Otunbayeva debated the complexities of the “great game” across Asia and the Middle East, the Egyptian American polemicist Mona Eltahawy, author of Headscarves and Hymens, opened a session on feminism with a rabble-rousing “Fuck patriarchy”, and went on to explain how “I want to talk about how as Muslim women we are reduced to what’s on our heads and what’s in between our legs,” holding a young audience rapt with a rhetoric that was thrillingly subversive.

“The real question is, who are the pigs?” said Hanif in reference to Orwell’s Animal Farm when talking about the trauma of partition in 1947. “We read that there were trains coming from Amritsar to Lahore that were strewn with dead bodies, but nobody talks about trains that left from here … That’s why Orwell matters as there should be people who stand up, who have the courage to say, ‘Hang on, this is not what happened. There is another side of the story and let me tell you that story.’”

If the weekend created a safe space for exploring dangerous ideas, it also opened up different cultures and other ways of seeing and being. Palestinian-American Susan Abulhawa, author of two Palestine-set novels, talked of the importance of love in a barbaric history of displacement and persecution; South Africa’s Zukiswa Wanner, author of a string of biting social comedies dealing with life in the post-apartheid world, joked about the irony of her work being deemed too un-African to be published in the west, while she herself was “too African” to be granted visas.

At a time when authors in the UK are questioning the value of literary festivals, and fretting about their failure to pay, it was humbling to see writers arriving with suitcases full of their own books to sell – the only way some of them can cross the territorial boundaries of the publishing world to reach an international readership.

For the outsider, the LLF revealed a picture of Pakistan that too often gets lost in reporting: a Sunday morning celebration of David Bowie brought pop nostalgists out in force, while literary groupies flocked to a session on Virginia Woolf, and many more turned out for two evening performances of AR Gurney’s Love Letters, a play about a 50-year correspondence between two east coast American blue-bloods.

On the way to a session showcasing English writer Emma Woolf’s work on the politics of anorexia, a young volunteer usher complained that her friends teased her about being tubby. “But I’m not – feel this,” she protested, proffering an iron-hard, gym-toned bicep. Among Sunday’s festival-goers discussion of the body and self-image could have filled a hall twice as big.

As the search booths were packed up and the Avari metamorphosed back into a five-star wedding venue, there was a palpable sense of happy exhaustion, of obstacles overcome and freedom defended. “How else could you experience so much of the world in a single weekend?” asked one visitor. The sole spot of trouble was splendidly and passionately literary, a Saturday night brawl between poetry devotees unable to get into an Urdu-language recital of work by the 19th-century poet Ghalib.